The following history of Lomita was written by Lomita resident, Brian C. Keith.

Early History of Lomita

The earliest known inhabitants of Southern California probably arrived before 9000BC, based on radiocarbon dates of artifacts found on the Channel Islands. Evidence of the earliest known indigenous inhabitants of Lomita and environs, the Gabrielino Indians, has been found in a village they called Suangna, or “Place of the Rushes”, near what is now the intersection of 230th Street and Utility Way in Carson. Remnants of this village remained even as late as the 1850s.

Lomita’s part in the Spanish period of California’s history begins in 1542, when Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo sailed into Bahia de los Humos, or Bay of Smoke as he called it, followed by Sebastian Viscaino in 1603, who renamed it San Pedro Harbor, after Saint Peter.

Things remained relatively quiet until 1784, when a Spanish soldier named Juan Jose Dominguez, a member of the Portola Expedition, requested and received permission to use 75,000 acres of land in Southern California from Don Pedro Fages, the Spanish Governor of California. Rancho San Pedro, the first land grant to be bestowed in California by King Charles III of Spain, stretched from the Los Angeles river to the Pacific Ocean and included what would become the cities of Carson, Torrance, Redondo Beach, Lomita, Wilmington, and parts of San Pedro.

At about the same time, the Sepulvedas established and started raising cattle on Rancho Los Palos Verdes, which caused quite a stir with the Dominguez family, as the Sepulvedas hadn’t actually received a land grant. They quarreled often, part of present day Lomita laying at the boundary of their dispute, which they didn’t resolve until 1841, when the Sepulvedas finally acquired and signed a deed.

The rancheros flourished until the 1860s, when a series of natural disasters hit Southern California:

- Too much rain in 1861

- Too little in 1862

- A paralyzing smallpox epidemic in 1862

- The ravaging of grazing lands by swarms of grasshoppers in 1863

- No rain in 1864

- The utter destruction of the region’s cattle herds by 1865

The rancheros foundered. Due to delinquent taxes and mortgage foreclosures, Rancho Los Palos Verdes was divided up and sold to 17 different buyers in 1882. Most of the land that constitutes present day Lomita was sold to a farmer named Ben Weston and the Ranch Water Company, which sheep farmer Nathaniel Andrew Narbonne, who was born in Salem, Massachusetts, owned. Narbonne received 3,500 acres.

Narbonne had moved to Lomita from Sacramento’s gold rush country in 1852. He had initially worked with General Phineas Banning in Wilmington and later, with partner Ben Weston, grew wheat and raised sheep on Santa Catalina Island.

Municipal History of Lomita

Credit: Lomita Historical Society Photo

Although there’s no question that Lomita derives its name from the Spanish for “little hills,” there is apparently some disagreement over just who originally bestowed the name.

One source claims Lomita was named by the early promoters of the district as they surveyed it from a hillside in Rancho Palos Verdes. Another source claims that “Lomita del Toro”, or “little hills of the bull,” appears on an early surveyor’s map of Rancho San Pedro, just a few miles east of the present day city, implying that Lomita inherited its name from the local fauna.

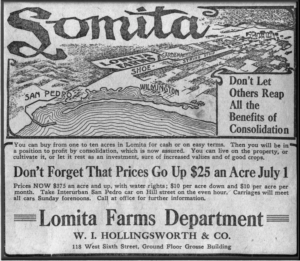

In any case, probably the biggest event in Lomita’s early municipal history occurred in 1907, when the W. I. Hollingsworth Company purchased a large tract of land just north of the Palos Verdes hills. The company intended to make the seven square mile subdivision a Dunkard colony after several of its clients, who were Dunkards, had expressed an interest in founding a settlement in the Los Angeles area.

In any case, probably the biggest event in Lomita’s early municipal history occurred in 1907, when the W. I. Hollingsworth Company purchased a large tract of land just north of the Palos Verdes hills. The company intended to make the seven square mile subdivision a Dunkard colony after several of its clients, who were Dunkards, had expressed an interest in founding a settlement in the Los Angeles area.

Development began soon afterwards. J. H. Pickering, a grading contractor, was hired to plow the roads and A. L. McSwain, a well driller, was hired to sink four water wells. Both men ended up living on the land they helped develop.

Other notable early settlers of Lomita include farmer M. M. Eshelman, considered by his peers to be the pioneer of the colony, and J. A. Smith, a miner and budding realtor (shown at left) who, in 1909, bought up 160 acres of land in Lomita and sold it for a nice profit to all of his Arizona mining buddies.

A school, general store (including a post office), and other businesses quickly followed. In 1909, the first churches in Lomita were built.

In 1921, heirs of Nathaniel Narbonne donated a parcel of property to Los Angeles on which to build a school to be named after their ancestor, which is today Fleming Middle School at 25425 Walnut Street. In 1958, Narbonne High School moved from Walnut Street to 24300 South Western Avenue in Harbor City.

Credit: Lomita Historical Society Photo

Just as Lomita has its share of players and pioneers, so it has its share of stories too.

In a scene reminiscent of the movie “The Two Jakes,” the water pump attached to the first well A. L. McSwain sank kept failing sporadically. C. B. Hollingsworth and H. E. Covert, Hollingsworth’s sales agents for Lomita, were called out to determine why. Covert took a seat near the water discharge pipe, musing. He lit a cigar and tossed the lit match near the pipe, which exploded in his face, nearly knocking him over. Little did he and the company realize at the time that that pocket of natural gas augured an oil boom that would change the face of Lomita forever.

Not that they weren’t given a few bizarre hints along the way. Mrs. Carvill, a local Spiritualist dubiously associated with the company’s principal, confided to him more than once that she had had visions of a “very black substance underneath the ground” on which McSwain was sinking the wells, and was worried that it might contaminate the water.

Notwithstanding premonitory explosions and Spiritualist visions, however, it took Hollingsworth and company sixteen years to figure it out. And even then they weren’t the discoverers. That distinction goes to a local character named “Tuck” Eaton. In 1923, Eaton sank a couple test oil wells on local land owned by Albert G. Sepulveda.

And proceeded to strike it rich.

Credit: Lomita Historical Society Photo

Property values skyrocketed. Lots that had originally been purchased for $300 to $400 sold for as much as $35,000. McSwain sold the ten acres he’d received for his services sixteen years earlier to the Los Angeles Board of Education for $80,000. When all was said and done, about 500 acres of the original tract of Lomita was given over to the oil industry. And never a dry hole was sunk.

Modern History of Lomita

Credit: Lomita Historical Society Photo

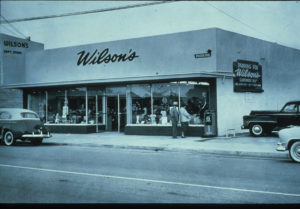

As Lomita emerged from the boom and bust of the 1920s and crept slowly into the 1930s, it soon acquired a new reputation as “Celery Capital of the World” (although some claim it could just as easily have acquired the title “Strawberry Capital of the World” as well). Truck farming of vegetables, fruits, and eggs became the prevailing occupation of Lomita residents in the 1930s.

In early 1935, a vaudevillian named Frank A. Gumm of Grand Rapids, Minnesota leased the Lomita Theater, which was located on Narbonne Avenue near 243rd Street, to present his singing and dancing daughters Mary Jane, Dorothy Virginia, and Judy, who would later change her name to Judy Garland.

Credit: Lomita Historical Society Photo

Other than its involvement in World War II, Lomita remained relatively quiet during the early 1940s. That quiet was disturbed in January 1944, however, when Army Air Corps pilot Merl Ogden, returning from a test flight of his Lockheed P-38 Lightning to the Lomita Flight Strip, now known as Zamperini Field, Torrance Municipal Airport, discovered that he couldn’t lower his landing gear. He subsequently ran out of fuel and crashed into Lomita’s Victory Garden. He died instantly.

After World War II, Lomita’s population exploded. As the 1950s progressed, adjacent cities, including the cities of Torrance and Rolling Hills, attempted to annex major portions of the original subdivision, Torrance succeeding.

Credit: Lomita Historical Society Photo

The Hot ‘n’ Tot, 1951

By the early 1960s, only 1.87 square miles of the original 7 square mile subdivision remained. And Torrance wanted more.

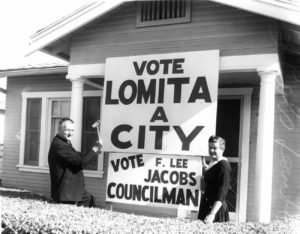

On June 30, 1964, after a couple of unsuccessful attempts, Lomita was incorporated as a city. In addition to halting annexation, incorporating was intended to curtail the development and construction of highrise apartments, a serious concern at the time. As one long time resident put it, “there was a definite feeling that this should be kept a small town and not just a subsidiary for a big city. Most of the people who came here have in mind family situations. If they come here, they don’t want a lot of swingers in apartments.”

The 70s and 80s passed without much incident. In 1989, 1993, and again in 1999, Lomita tried unsuccessfully to withdraw from the Los Angeles Unified School District, claiming it wanted more control and better management of its schools’ curriculum and spending. In 1990, the City had better luck with the County of Los Angeles, seceded from the water district, and assumed complete control and operation of Water District 13.

Although it’s shrunk from its original 7 square miles to a meager 1.87 square miles, Lomita has managed not only to survive, but to mature. Boundary disputes, land divisions, natural disasters, civil wars, world wars, and cold wars, oil booms, stock market busts, and even annexation to surrounding communities couldn’t consume little Lomita.

From a simple ranch house and a few out-buildings on the Narbonne property, a sleepy narrow gauge electric railroad stop on Western Avenue, and a handful of dirt roads named after trees and fruits, Lomita has grown into a small city and, in spite of that growth, managed to maintain its rustic, small-town flavor.

San Pedro Trolley Line, Early 1900s

Sources: History of the Harbor District of Los Angelesby Ella A. Ludwig, 1927; Lomita: Scenes from a California Town, Financial Federation, Inc., 1978; February 7, 1997 Los Angeles Times article (page B2) by Cecilia Rasmussen; January 1, 2000 Daily Breeze article (page M23) by Carmen Marinella; Lomita Adopted Annual Budget 1998-1999; various web pages